If you’re training for a big mountain, wearing a GPS fitness watch that spits out daily physiological metrics, you’ve probably asked yourself this question (sometimes proudly, sometimes nervously):

“Is my VO₂ max good for my age?”

It’s a fair question. VO₂ max has become the vanity metric of endurance sports. It’s clean. It’s numerical. It’s easy to compare. And platforms like Garmin, Apple, COROS, SUUNTO, Firstbeat, etc. have turned it into a fitness scoreboard you carry on your wrist.

But here’s the quiet truth I want to reframe early:

VO₂ max is rarely the reason capable, disciplined adults fail at altitude or endurance goals.

The limiter is almost always how that oxygen is utilized—by the lungs, the breathing muscles, and your nervous system as a whole—not just how much oxygen your heart could theoretically deliver.

This article will still answer the question you came for. We’ll look at VO₂ max by age, what the charts actually show, and what “good” really means, especially into your 50s, 60s, and beyond.

But more importantly, I’ll show you:

- Why most people misinterpret VO₂ max

- Why traditional training often fails older endurance athletes

- What actually limits performance at altitude

- And how to beat the chart (without chasing junk miles)

The problem most people misunderstand about VO₂ max

VO₂ max measures the maximum amount of oxygen your body can use per minute, relative to body weight (ml/kg/min). In a lab, it’s determined during a maximal test—usually on a treadmill or bike—where intensity ramps until you simply can’t continue.

Physiologically, VO₂ max reflects:

- Cardiac output (how much blood your heart can pump)

- Oxygen-carrying capacity of your blood

- Ability of muscles to extract and use oxygen

That sounds important—and it is. But here’s what gets lost:

VO₂ max is a ceiling. Most endurance events, climbs, and long summit pushes happen far below that ceiling.

At altitude especially, performance isn’t limited by peak capacity—it’s often limited by additional factors:

- Ventilatory efficiency

- Breathing mechanics

- CO₂ tolerance (and underlying Bohr effect of oxygen extraction by muscle tissue)

- Nervous system regulation under stress

Now THAT doesn’t show up on a VO₂ max chart… 😀

VO₂ max by age: what the data actually shows

Let’s ground this in reality before we critique it.

Across large population studies, VO₂ max does decline with age, roughly 8–10% per decade after 30 if untrained. The good news? Regular endurance training dramatically slows that decline.

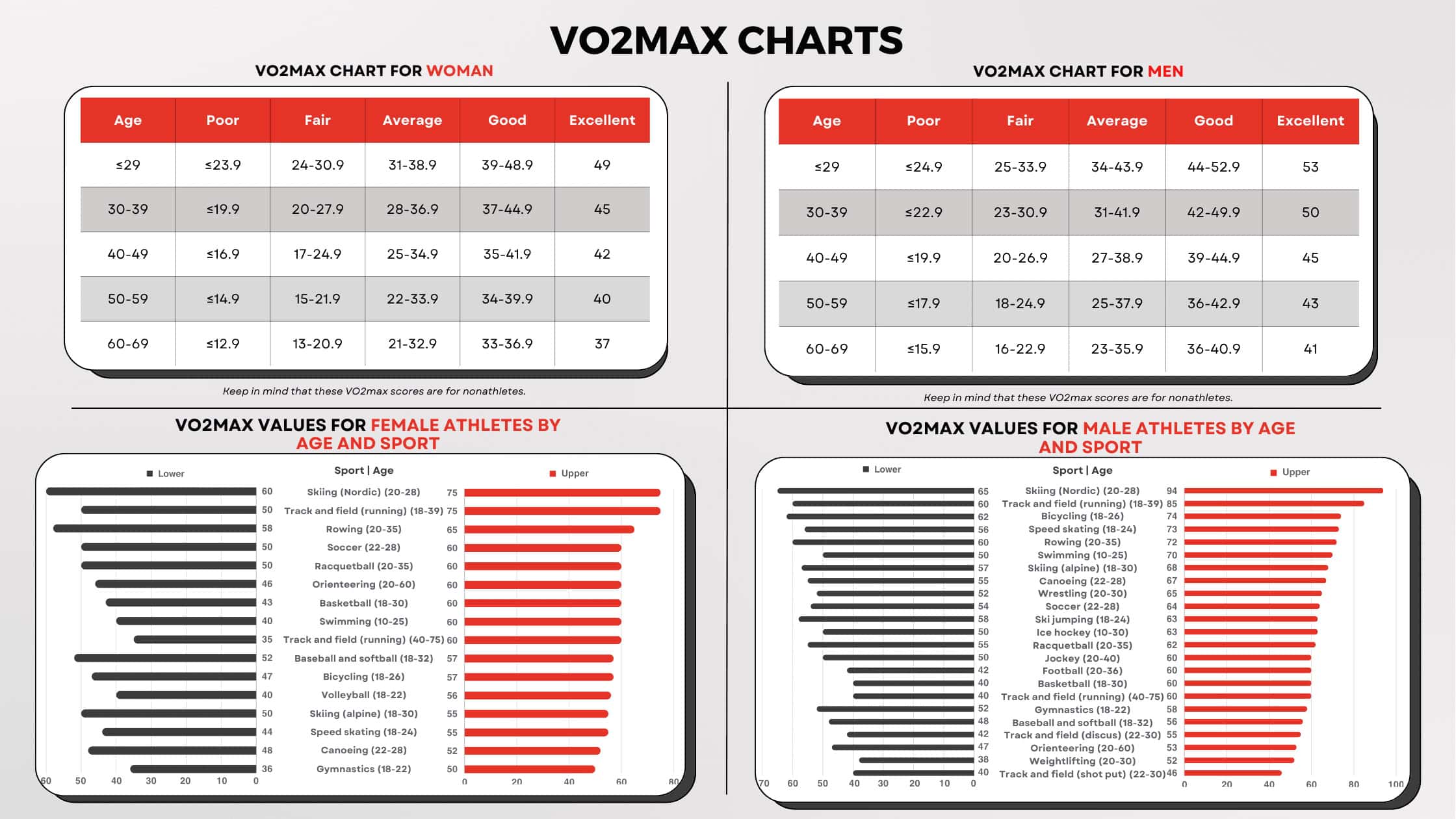

Below is an over-simplified reference chart combining population norms and endurance-trained adults (men and women averaged). Values vary by source, but the ranges are consistent across major datasets (Firstbeat, Inscyd, clinical exercise physiology literature).

VO₂ Max Chart by Age (Approximate)

| Age | Average | Good | Excellent |

| 30–39 | 35–40 | 45–50 | 55+ |

| 40–49 | 32–37 | 42–47 | 52+ |

| 50–59 | 28–34 | 38–43 | 48+ |

| 60–69 | 25–30 | 35–40 | 45+ |

| 70+ | 20–25 | 30–35 | 40+ |

So yes—if you’re 55 years old with a VO₂ max of 45, you’re well above average. That’s objectively good.

But now comes the important question:

Does that number actually predict success on a mountain?

Often, no.

The altitude reality check

High altitude doesn’t care how fit you are at sea level.

At altitude:

- Barometric pressure drops

- Oxygen saturation falls

- Breathing work increases

- CO₂ clearance takes precedence over O₂ diffusion

This means your limiting factors shift away from the heart and toward the respiratory system and nervous system.

I’ve worked with plenty of athletes who:

- Had VO₂ max values in the “excellent” range

- Still felt wrecked above 14,000 feet (4,200 meters)

- Developed anxiety-driven breathing patterns

- Couldn’t sustain pace despite strong legs

And I’ve worked with others who had average VO₂ max scores—but excellent breathing efficiency—who moved calmly and steadily at altitude.

Why common training approaches fail (especially after 50)

If you’re over 50, you’ve probably done some version of this:

- More Zone 2 miles

- Occasional high-intensity intervals

- Strength training when time allows

- A hope that “fitness will carry me through”

This approach works—until it doesn’t.

What changes with age isn’t just VO₂ max. It’s:

- Reduced lung capacity

- Weakened respiratory muscles

- Lower CO₂ tolerance (with stress-driven over-breathing especially)

- Greater sympathetic (stress) activation under load

None of those are fixed by adding more miles.

In fact, piling on volume without addressing breathing often makes things worse—more fatigue, poorer recovery, and a nervous system that’s always slightly overcooked.

What’s actually limiting performance (and why VO₂ max misses it)

Here’s the hierarchy I see over and over in endurance and altitude athletes:

- Breathing mechanics

Shallow, chest-dominant breathing wastes energy and limits Oxygen/CO₂ exchange. - CO₂ tolerance

Most people feel “out of breath” not because of low oxygen—but because CO₂ rises. Poor tolerance drives panic breathing, early fatigue, and poor muscle oxygenation. - Respiratory muscle fatigue

At altitude, your diaphragm works harder. If it’s weak, ventilation collapses before the legs do. - Nervous system regulation

Anxiety and sympathetic overactivation increase breathing rate, decrease efficiency, and spike perceived exertion.

VO₂ max doesn’t diagnose any of these.

Why diagnostics matter before more effort

This is the core Recal philosophy:

Diagnosis → clarity → confidence → correct training

Before prescribing more intensity, more volume, or more suffering, you need to know what’s actually limiting you.

That’s why we built the Recal Breath Index (RBI)—to identify the single weakest link in:

- Breathing mechanics

- CO₂ tolerance

- Respiratory muscle strength

- Breathing pattern under stress

When our athletes fix their weakest link, performance improves—often without increasing VO₂ max at all.

And paradoxically, VO₂ max often improves as a byproduct, not the target, because we’re actually targeting the underlying weak link.

How to “beat” your VO₂ max for your age (without chasing the chart)

If your goal is endurance, altitude readiness, and long-term health—not bragging rights—here’s the smarter approach.

1. Improve oxygen use, not just oxygen delivery

Better breathing mechanics and stronger respiratory muscles mean:

- Higher oxygen saturation at submax workloads

- Less wasted ventilation

- Lower heart rate for the same output

That’s functional fitness.

2. Train CO₂ tolerance

Raising your tolerance to CO₂:

- Reduces perceived breathlessness

- Delays ventilatory panic

- Improves pacing under stress

This is especially critical at altitude, where CO₂ clearance is impaired.

3. Build respiratory muscle strength

Lower air pressure = more work for the diaphragm.

Targeted respiratory muscle training has been shown to:

- Improve oxygen saturation at altitude

- Reduce respiratory fatigue

- Improve endurance performance

This matters far more than squeezing out another VO₂ max point.

4. Regulate the nervous system

Calm, controlled breathing under load:

- Reduces sympathetic overdrive

- Improves decision-making

- Conserves energy

That’s summit fitness.

Longevity, VO₂ max, and healthspan

There is good news for the data-driven crowd:

Higher VO₂ max is strongly associated with:

- Lower cardiovascular disease risk

- Lower all-cause mortality

- Better functional independence with age

But again—the studies don’t suggest you need elite numbers. The biggest health gains come from moving out of the low VO₂ max categories into moderate or good ranges.

In other words:

You don’t need to be exceptional. You need to be efficient and consistent.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a good VO₂ max by age?

A “good” VO₂ max depends on age and sex, but for most adults over 50:

- High 30s to low 40s is solid

- Mid-to-high 40s is excellent

Context matters more than comparison.

Is a VO₂ max of 50 good?

Yes—at almost any age, a VO₂ max of 50 is very strong. But it doesn’t guarantee altitude performance without efficient breathing.

What is Michael Phelps’ VO₂ max?

Reported values range from the high 70s to low 80s ml/kg/min—elite, genetic outlier territory. Not a useful benchmark for mortals.

Can VO₂ max be improved after 50?

Yes, modestly. But the biggest performance gains usually come from improving efficiency, not chasing the ceiling.

Does losing weight improve VO₂ max?

Sometimes, because VO₂ max is expressed relative to body weight. But that doesn’t always translate to better performance or resilience.

Do people with high VO₂ max live longer?

Yes—especially compared to those with very low VO₂ max. The relationship is strongest at the low end, not the elite end.

Final thought

VO₂ max is a useful metric—but it’s a blunt instrument.

If you’re a 50 or 60+ year-old athlete preparing for a serious climb, your success won’t hinge on whether your VO₂ max is “excellent” on a chart.

It will hinge on:

- How well you breathe under stress

- How efficiently you manage oxygen and CO₂

- How calm your nervous system stays when the air thins

Get those right, and you’ll often outperform athletes with higher numbers—and enjoy the process to the summit far more!